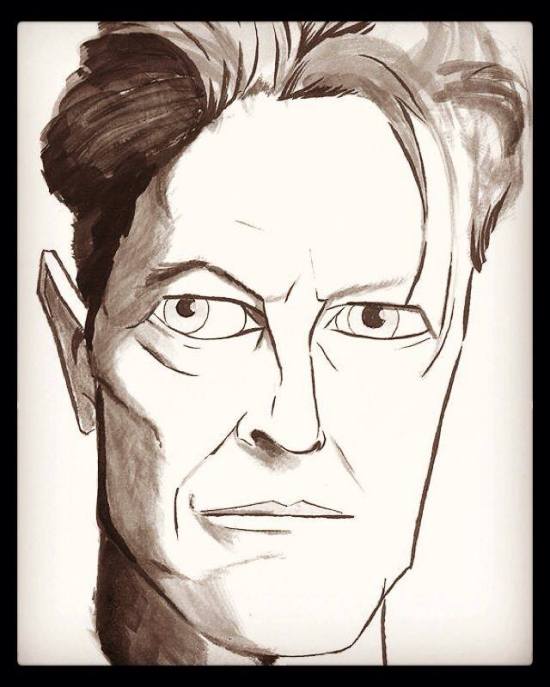

David Bowie (original art by Aaron Alex King)

I can’t remember the first time I heard a David Bowie song. My parents tell me that I insisted upon repeat viewings of Labyrinth as a child, and while I’m sure that this is true, I can’t recall it with any specificity. There was never a holy moment: no song playing on the radio that stopped time, no music video that transfixed my attention. Bowie’s presence in my life was less a romantic relationship with a definite start, and more a familial one, ever present. And like family, Bowie was easy to take for granted. His music was like an uncle, one I always knew, but didn’t really recognize as being anything extraordinary until I was nearly an adult.

I began to recognize the genius of Bowie’s work around the same time that I began to appreciate the medium of comic books. The timing was seemingly coincidental: an affinity for Neil Gaiman’s prose works led me toward his astounding comic book output, while at the same time, I was turning to theatre for a creative and social outlet. I suspect most theatre nerds have a huge amount of respect for David Bowie, but it wasn’t the performance aspect of Bowie’s work that got me paying attention to him for the first time. It was his voice. Theatre forced me to learn how to sing, and I realized that I sang a little like David Bowie. Thus, when I learned to sing, I learned to sing David Bowie.

While two different roads led me toward an affinity for both Bowie and comic books, I think it’s much less a coincidence that my adoration for both have endured well beyond that. Bowie’s particular brand of artistry certainly has some parallels to Neil Gaiman’s weird and fantastic Sandman epic, and while one provided the soundtrack to the other during my latter adolescence, I’ve come to recognize that Bowie’s impact upon me has more in common with an altogether different comic book property: X-Men.

I was, again, a late arrival to X-Men fandom. Sure, as a child during the ‘90s, I watched the wonderfully terrible X-Men cartoon, and I enjoyed Bryan Singer’s films well enough. The cartoon and the movies just hadn’t done enough to convince me that the X-Men were anything special, and even as the space on my bookshelves dedicated to comics grew to surpass that dedicated to other books, none of those books were X-Men books. I ought to mention that I was only buying trades for probably about the first five years of my comics fandom. It wasn’t until I was studying illustration for sequential art at Max the Mutt that I began to buy comic books in single issues. Unsurprisingly, while in art school, I was very art-forward in my comics tastes, and if an artist whose work I enjoyed was drawing a book, I would buy it regardless of what characters it featured. Thus, when All New X-Men debuted with Stuart Immonen handling the art, the book went straight to the top of my pull list. After just a few issues, the X-Men, drawn by Immonen or not, cemented themselves as some of my favourite superheroes.

Art by Stuart Immonen, from All New X-Men (Vol. 1) #2

The X-Men, it seemed to me, were a perfection of the superhero narrative. Yes, Superman is indisputably the perfect superhero, but this motley crew of mutants seemed to better demonstrate some of the inherent appeal of the genre. Superman, after all, is an aspirational figure – by which I mean, we don’t really relate to Superman, we are inspired by Superman. The X-Men, though, are an absolute mess. Their relationships are dysfunctional. They make mistakes and bad choices. They struggle to do the right thing, but don’t get any adulation for their heroism – they are, as the tagline goes, hated and feared. Superman is something better. The X-Men are something other.

Hannah Hart, the noted YouTuber behind My Drunk Kitchen who is also a comic book geek and all around delightful human being, observed in an interview with Out: “The superhero story has evolved into a story about a hero for the outsider.” Hart goes on to explain:

The whole mutant saga is based on something that marks these people different, often on the outside. There is something special about them, something different. As a queer kid growing up, I didn’t really know why I liked superheroes so much. Now I think a part of it was that I liked seeing how they dealt with being an outsider.

I think Hart really touches on something that draws a lot of people toward superhero stories, and it’s that precise quality that X-Men does better than just about any other. This, too, is the precise thing which links the X-Men, in my mind, with David Bowie.

David Bowie always presented himself as something other. He was a man of many characters and many faces, but none was the everyman. He treated even his gender as an aspect of performance; in an obituary for The Conversation, Rebecca Sheehan observes:

Bowie helped to empower audience members who felt different. By making androgyny and bisexuality fashionable in the public realm, Bowie helped to create a safe zone in which, by dressing up similarly, fans could explore their gender and sexual identities without necessarily being labelled or identified.

But, it’s important to note, Bowie himself was not gay (despite stating otherwise in a magazine interview in 1972). In my view, his actual sexuality is pretty well irrelevant, in much the same way that a specific analog for the mutant metaphor in X-Men is wholly irrelevant to its meaning. Of course, this hasn’t prevented many from trying to draw a direct correlation. Bryan Singer, in his X-Men movies, leaned toward using mutants as a metaphor for homosexuality. In his current run on Extraordinary X-Men, Jeff Lemire seems to be trying to draw the same comparison, drawing some pretty clear parallels between M-Pox within the mutant community to AIDS in the gay community. Others try to make it an analogy for civil rights, clumsily comparing Xavier to Martin Luther King Jr. and Magneto to Malcolm X. But as J. Rachel Edidin and Miles Stokes, the world’s leading X-perts and hosts of the absolutely wonderful podcast Rachel & Miles X-Plain the X-Men, none of these allegories are functional. In their third annual Giant-Size Special episode of the podcast, Jay commented regarding the civil rights analogy, “I don’t think it was ever apt.”

Miles agrees, but points to his own bio on the podcast’s website: “Buy him a drink and he’ll spend the next two hours telling you about how Chris Claremont made him a feminist.” He describes how, though he himself wasn’t part of a particular minority group for which mutants are used as a stand-in, reading X-Men comics as a child helped him empathize with people who aren’t like himself. Jay continues, “I will say that the allegorical generality is valuable . . . the odds of finding a character who reflects every reader who needs that point of identification is very low, but when you have someone who is outside of that and different in other ways, it becomes easier for a wider range of folks to put themselves in their shoes.”

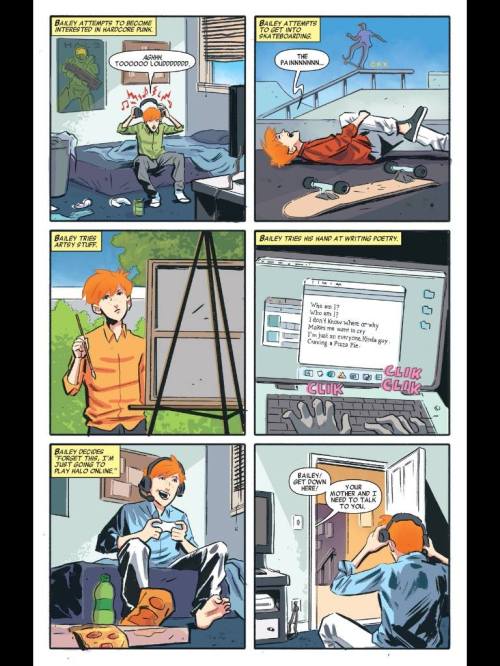

I can attest to this personally; a white, cisgender and heterosexual male, I am within the prevailing majority, at least in superficial terms. But most of my life, I was always positioned on the outside of things – home-schooled straight from kindergarten to completion of high school, I grew up in relative isolation. I didn’t mind in the least, but to this day, I find myself without the same foundation of common experiences that most people use to identify with each other. Thus, the sort of outsider narratives being related in Jason Aaron’s Wolverine and the X-Men, and Brian Michael Bendis’s companion All-New and Uncanny X-Men books, really resonated with me. It’s this same quality that is delightfully on display in Max Bemis and Michael Walsh’s current miniseries, The Worst X-Man Ever.

Art by Michael Walsh, from X-Men: The Worst X-Man Ever #1.

David Bowie, in similarly general terms, made a performance of this same message across multiple platforms. In the Conversation obituary, Rebecca Sheehan writes, “Through playing with notions of authenticity and identity, Bowie challenged ideas of normal and natural. He made explicit in popular music that identity could be imagined by individuals, rather than dictated by society.” It is this, the value and self-determination of the individual at odds with society, that is a prevailing theme throughout X-Men. Both Bowie and the X-Men, too, deliver a similar message. Sheehan concludes:

Ziggy Stardust forgives and encourages connection, transgression and rebellion in his listeners. For many he has fostered communities of belonging and hope. In his various personas, David Bowie enabled the imagining of new selves. “It was not only music,” one fan wrote of what Bowie inspired, “it was a way to be.”

His legacy on record sings across time, space, and now mortality with this simple message: “You’re not alone”.

And we’re not.

Don’t forget to follow Gutterball Special on Facebook and Twitter!